One of the most important strategies for improving your health is to grow your own food. However, that may not be so easy if you’re unaware of the importance of soil microbes.

Wendy Taheri is a research microbiologist, to whom I was introduced via Gabe Brown, a farmer in North Dakota, who is a strong proponent of regenerative land management.

Taheri was formerly employed at the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), and she recently founded a new company, TerraNimbus, to help farmers enhance their yields, reduce inputs, and improve nutrient use efficiency (NUE).

“I got my PhD in ecology and evolutionary biology at Indiana University,”Taheri says. ”I was doing restoration work at old coal mines to make the soil grow plants again. We were focusing on using microbes for restoration.

During an experiment, I saw that the microbes I used were able to increase plant biomass by 69 percent. I said to myself, ‘Wow, we’ve got to get this to the farmers.’ After I graduated, I took a job with the USDA to try and do that.”

In this interview, she discusses the importance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi(AMF). According to renowned mycologist Paul Stamets, 70 percent of the soil microbes are fungi, so they’re a really critical consideration when you’re trying to improve soil health.

What Are Mycorrhizal Fungi?

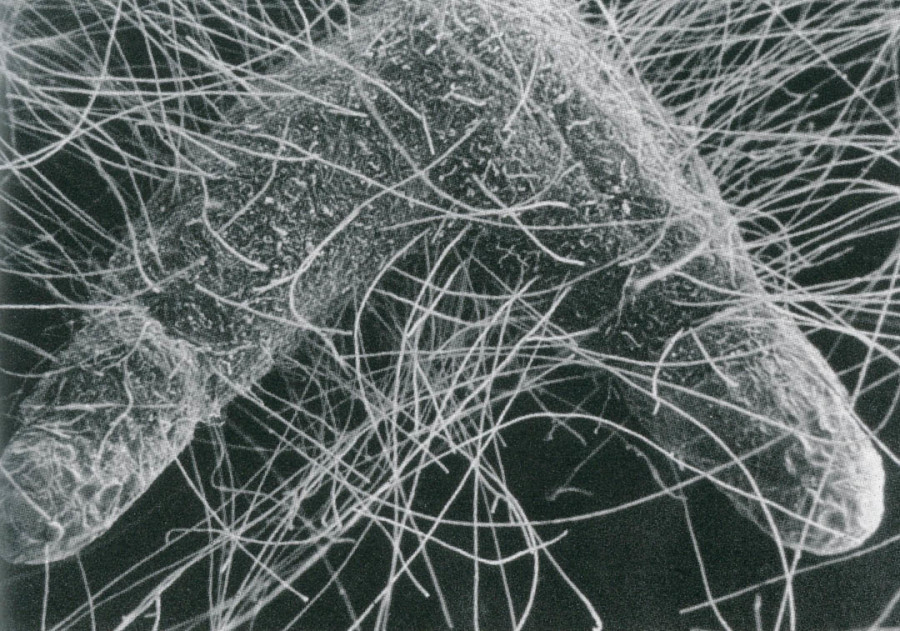

While few people have actually seen mycorrhizal fungi, as you need a microscope to see them, they are a very important foundation for healthy soils. Their spores are in the soil and their hyphae (long, branching filamentous structures) are not only in the soil; they also integrate with the plant via its roots.

The filaments penetrate the roots of the plant and get inside the cells where they grow an organ called an arbuscule. There are seven different kinds of mycorrhizal fungi, but arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are the most important to farmers, as they are associated with so many different plants.

While the arbuscular kind associates with 90 percent of plant families, the other six kinds are more specialized for specific plant groups.

The hyphae, which are integrated into the plant, branch out into the soil, acting like very fine roots, giving the plant access to a larger volume of soil and hence more nutrients. These filaments specialize in uptaking nutrients such as trace minerals, particularly phosphorous, which is a limited resource.

Mycorrhizal Fungi as an Ecological Solution to Pollution

When phosphorus is applied as fertilizer, only a portion of it is utilized by the plants. A lot of what is being applied ends up running off and spilling into waterways, as tilling promotes soil erosion and hinders water retention.

From various waterways, phosphorous and other agricultural nutrients and chemicals eventually end up in our oceans, where they can lead to oxygen depletion (eutrophication).

“We tend to put a lot of phosphorus in our soils and use it not as wisely as we could, or as conservatively as we should,’ Taheri says. This is really important because we’re going to run out eventually…

Our soil, our atmosphere, our water, our oceans, our streams, and our lakes are all interconnected through nutrient cycles…

It’s my opinion that everyone who eats food or breathes oxygen should be concerned with how we manage our agricultural complex because the soil and the organisms in it is the only system large enough to offset global warming, which affects us all.

AMF are drawing carbon through plants, via photosynthesis. The plant is taking carbon out [of the atmosphere]. It’s feeding carbon in the form of sugars to mycorrhizal fungi. In fact, they get 100 percent of their carbon from the plant.

And then they utilize that carbon to build soil structure, which increases the soil quality. It’s the best way to sequester carbon, and it’s the only system big enough to offset all the oil we burned over the last century. We could actually do that.

A group of scientists is working on demonstrating that how we manage our soil can affect how much carbon we can store in it. And mycorrhizal fungi use that carbon to form soil aggregates, which is how we build our soil structure. They are keystone species in the soil; they’re very important.”

Tilling the soil promotes runoff, allowing a lot of phosphorus to wind up in the ocean. But matters are made even worse by the fact that we also have so much carbon dioxide in the air. This carbon dioxide forms carbonic acid when it mixes with water, making the water acidified.

Few people realize that 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe actually comes from the algae in the ocean, and acidification may be affecting the microbes and algae responsible for the production of this oxygen…

“Balancing global warming, carbon dioxide through management of agricultural systems can solve a lot of problems for humanity,” Taheri says.

The Importance of Soil Carbon for Water Retention

About 20 years ago, scientists discovered a glycoprotein called glomalin, which adds to soil aggregates. It is produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

“If you don’t have aggregates, you have dust and everything goes away. That’s not a good soil for farming. Aggregates are little glued-together particles that don’t fit together and compact. This is how we alleviate compaction,” Taheri explains.

“And the pore space is what allows drainage and air to get into our soil because plant roots need air and many of the microbes that are important to plants do too.”

Those pore spaces are also what determine, to a great extent, the water-holding capacity of the soil. It’s actually the carbon in the soil that permits water to be retained. Much of that carbon occurs as what we call soil organic matter (SOM). As the carbon content in the soil declines along with SOM, so does its ability to hold water, making us more subject to problems from both droughts and floods.

When there’s flooding, the soil cannot absorb the water and hold it for when there’s a drought later. Instead, all the water runs off the top, taking the topsoil with it, and the topsoil is the most biologically active, most nutritious, and most valuable part of the soil profile.

As discussed in a previous interview with Gabe Brown, in North Dakota he gets about 16 inches of rain each year, most of which falls in a day or two. Because of his no-till farming practices and the improved soil structure he’s achieved with his regenerative land management, he’s actually able to retain almost all of that water, whereas his neighbors struggle with runoff and topsoil depletion.

That’s also why cover crops, and diversification of crops, are so important in protecting and improving the quality of soils. We also need to limit our use of chemicals in agriculture, as they tend to destroy important soil fungi.

“Individual families of mycorrhizal fungi are more sensitive to some chemicals than others,” Taheri says. “We tend to put a lot of different chemicals into our [mono]cropping systems. What I have seen is a decline in numbers, a decline in diversity, and a dominance by certain species [of fungi] in our agricultural complex, which means we’re not getting all the benefits we could out of it.”

Growing Organic Foods Is Part of the Small- and Large-Scale Solution

One of the steps nearly everyone can do to help increase the fungal growth in the soil is to buy and consume organically-grown foods. Those who are willing can take it a step further, because the fact that something is organically produced does not mean that no-till strategies or cover crops were used. The next step is to either grow it yourself, or find a farmer who is integrating these important land regeneration practices.

“Randy Anderson, a weed scientist for the USDA at ARS has done a lot of research on cover crops that can be used to suppress weeds. If you go cool season-cool season followed by warm season-warm season, he told me that over the course of a few years, you’ll deplete that weed seed bank and won’t have a weed problem anymore.” But it’s hard to get farmers to switch over from what they know works and try something new, although Gabe Brown, myself, and many others are trying to help them make that switch,” Taheri says.

Modern Crop Breeds are Losing Mycorrhizal Association, Which May Prevent Us From Becoming Sustainable

Aside from using no-till practices and cover crops, we need to reduce the amount of phosphorus used, because too much phosphorus suppresses the plants association with mycorrhizal fungi. One of the problems Taheri is seeing is that modern crops, probably bred under high-input breeding systems, has led to plant species that are no longer sensitive to mycorrhizal association.

This means the ability of the plants to form the association with mycorrhizal fungi is being bred out of them. In March of this year, Taheri is starting a seed certification program for commercial growers that will score whether or not, and how well associated with mycorrhizal fungi various seed varieties are.

“Any commercial growers can send me seeds and say, “I want to know how well these guys respond. If we lose that symbiosis—because of the nutrient use efficiency that is created by these microbes, and their important position in the soil—and they start to die out in our soils, I don’t think we will ever become sustainable, which means our residence here as a species on the planet will be numbered, as far as how many years we have left. We have to be able to grow enough food and we can’t really afford to lose this association.”

Some people counter such arguments by saying that we can shift to alternative growing methods, such as hydroponics. However, shifting all agriculture to hydroponics is unlikely to work on a large scale. And you still have problems like runoff to deal with. It’s not entirely ecologically sound.

Also, that’s not the way food was historically grown. That’s not to say you can’t produce some decent food using hydroponics, if done properly. But without this association with mycorrhizal fungi and other soil microbes, it’s difficult to imagine optimally healthy and nutritious plants being produced, because there’s such a dynamic, complex symbiosis that occurs to improve the health of the soil and nutrients that it provides us.

“Now, humans are doing the work of nature. Instead of looking at nature and saying, ‘How can I get nature to do this as part of the balance of how I’m growing my plants?’, instead… we’ve been doing nature’s job with chemicals. Well, we inevitably have discovered we’re not as good as Mother Nature and there are side effects to what we’ve done. We have to be careful, because look at the size of our agricultural complex; it’s a third of the terrestrial surface of the world. It is the largest ecosystem on the planet. We have to take a real serious look at the impact of that system on our water and air quality. We can’t ignore it, it’s too big.”

Benefits of Mycorrhizal Fungi

Most of commercial agriculture is focused on increasing yield, but according to Taheri, we really need to be looking at improving the mycorrhizal association, and breeding our microbes and our plants together to work as a team. Doing so can produce tremendous benefits, including but not limited to the following:

Increased soil fertility Increased essential oil production Increased water-holding capacity Protection from both fungal and bacterial diseases Reduced soil compaction Drought tolerance Heavy metal tolerance Salinity resistance Higher nutrient content Increased biomass Reduced inputs, meaning decreased need for harmful chemicals Earlier flowering; increased flowering, and more fruits Reduction or elimination of runoff and leaching Carbon sequestration, which will reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide

How to Encourage Mycorrhizal Growth in Your Garden

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which are the focus of this article, are primarily associated with vascular plants, this includes the vast majority of everything we eat. (Notable exceptions are the Brassicas and Amaranth families.) The mycorrhizal fungi that associate with trees are from other groups of mycorrhizal fungi. For example, pine trees associate with a group we collectively call ectomycorrhizae, while the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are often referred to generically as endos or endomycorrhizae.

AMF, or endos cannot live without host plants, which is why cover crops are so important. There should always be living roots in the ground to support your microbes. There are mycorrhizal fungi inoculants that you can buy for your home garden, but according to Taheri, you need to be aware that when using soil inoculants, they’re competing with all the microbes already in your soil that have adapted to your current soil conditions. The scales of success are already tipped against them because they’re not pre-adapted.

As noted by Taheri:

“Most of the inoculants that I have seen are the same group of 12 species that are being recirculated. One of the species, for instance, is deserticola. It’s from the desert; the name tells you that. If Glomus deserticola is put in some place very different from the desert, what are the odds it’s going to survive? It’s kind of like putting a polar bear into the desert and expecting it to do well.”

That said, if you get a good association between plant and mycorrhizal fungi, you can potentially double plant growth. But most of the inoculants currently on the market are not the most appropriate species. Taheri has a very large assortment of fungi in her own collection, and has started working on a commercially viable formula. However, it may still be years before it’s perfected. Compost teas are also ineffective for promoting mycorrhizal fungi. So what can you do to improve the fungal composition of your soil?

“The best management practices for mycorrhizal fungi are cover crops, above-ground diversity, and no-till,” Taheri says. “Minimize your soil disturbance, because you’re breaking up your hyphae—which is not so good for your plants—as soon you start digging around.”

As far as inoculants go, most of them are, to a large degree, one species called Rhizophagus intraradices. If you use fertilizer, you will typically already have plenty of Rhizophagus. It is well adapted to agricultural conditions. So why pay a lot of money for it? Taheri recommends avoiding inoculants containing primarily Rhizophagus for this reason. Inoculants can be helpful if you’re buying pottings.

However, as these have typically undergone a process that makes the soil fairly sterile. If you already have healthy soil, then you can further propagate mycorrhizal fungi simply by increasing the diversity of plants in your garden. Earthworms are a very good indicator of healthy soil. Also check your garden for insect predators, such as lizards and spiders. They too are an indication of a healthy soil balance.

“When you have diversity, you have homes for a lot of different kinds of organisms, and that’s when your predators start to come in. That keeps everything in balance,” she explains. “It doesn’t matter that you have insects that are eating a leaf here and there. What matters is whether or not it gets out of hand. Most of the time, pathogens and things that grow on your plants are always present. Most of the time, they don’t have much impact because things are in balance. You want to make sure that your management practices are not favoring things that are eating your plants while disfavoring the things that hunt those things that eat your plants.”

More Information

Taheri’s company, TerraNimbus, is still new and does not yet have a working website. Eventually, she’ll have a YouTube channel that will provide helpful videos for farmers and laypeople, including interviews with scientists and leading innovators; so you can check for that from time to time or get on their mailing list. She’s also writing a booklet for farmers and gardeners about mycorrhizal fungi and what growers should know about them.

In addition to the seed varietal testing TerraNimbus will provide, they’re also planning a Rocket Hub campaign for which they need supporters to help continue mycorrhizal research and develop truly effective inoculants to restore our nation’s soils. If you would like to be on their mailing list you can sign up at terranimbus.com.

For a video experience of this info, please see: Dr. Mercola Interviews Dr. Taheri (Full Interview)